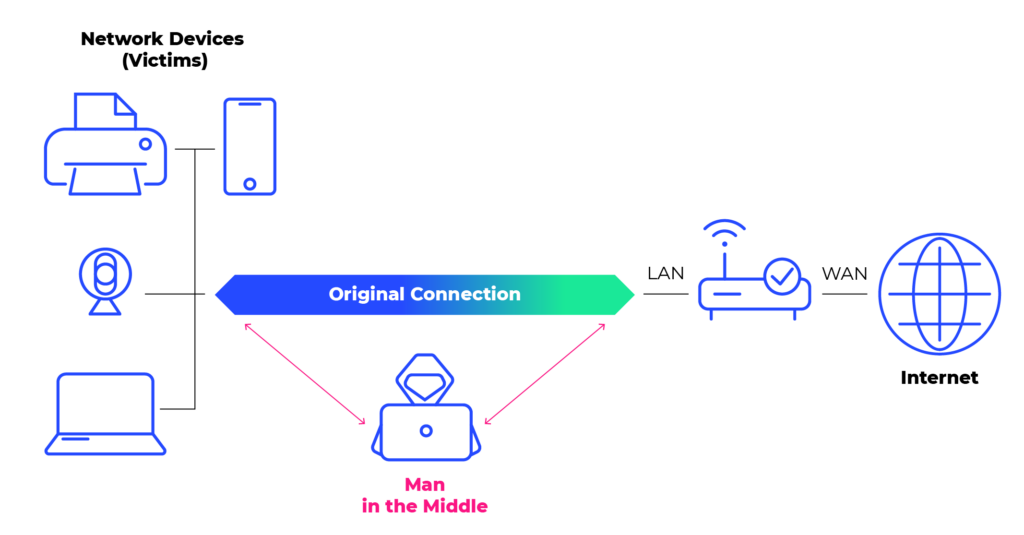

Hackers can use many types of security threats to exploit insecure applications and customer premises devices such as servers, printers and even high-tech, connected coffee makers (yes, they exist!). Threat actors can run some of these attacks using automated software, while others require a more active role from attackers. This article focuses on environments in which smart devices could be leveraged by perpetrators, to position themselves in a conversation between a user and an application. The lack of security at network level in environments such as homes, micro-SMBs and even public or smart cities networks, is a growing concern. In this deep-dive review we will reveal what it takes to detect and prevent Man-in-the-Middle attacks on various IoTs, in order to protect your customers privacy and data.

Fans of the brilliant USA Network television series, Mr. Robot, may not realize that an example of an “active” attack was portrayed quite often through the 45-episode run, namely a “man in the middle” (MITM) attack. Elliott Alderson, portrayed by Oscar®-winning actor Rami Malek, and his colleagues would compromise servers and other equipment with MITM techniques in order to steal credentials and gain access to the sensitive information they were looking for.

Here are some components of an MITM attack: hijacking online sessions of various types, injecting agents or bots in the middle of an ongoing legitimate exchange of data, intercepting confidential data, leveraging the real-time nature of these transactions to go undetected and using “impersonation” to trick users with malicious links and data.

This article focuses on several areas of growing concern of unmanaged networks: homes and SMBs (e.g., SOHO), open spaces as in large factory floor areas and smart city outdoor environments, and the rising risks found in the use of Raspberry Pi and Arduino to enhance various connected devices.

The Remote Command Injection Hack

On the “home front,” one MITM technique involves “remote command injection” (RCI) in, for instance, a printer connected to a router. With RCI, a PC could think the printer is a router, by committing an ARP Poisoning Attack, then the printer alerts the hacker about opportunities such as online sessions with a bank or other destination which might reveal sensitive information. To assist in this malfeasance, the MITM code here would also ask the PC if it has all the latest security patches and related protection. If not, the vulnerability could cause information disclosure if an attacker injects unencrypted data in the target secure channel between the targeted client and a legitimate server.

Further, MITM hacks on small businesses could be “stepping stones” into gaining access into the larger business or bank partners of these entities. In home, SOHO and SMB settings, MITM hackers can gain lots of data or “intelligence” even if they are not directly “stealing” from the SMB. For instance, in the case of a connected smart device, an RCI placed into such a device in the office of a high-powered legal firm could be used to gain information about the firm’s clients. And similar opportunities could exist in all kinds of environments where securing connected devices might not be the highest priority, such as doctors’ offices, single or multi-branch retail shops.

Another target that is becoming an increasingly attractive target is a device with high processing power or “CPU muscle.” Good examples of such devices are IoT-connected equipment like 4K HD cameras and 3D printers. Equipment like this processes lots of information, has weak security safeguards – and is found in areas such as factory floors (3D printers, as well as robotic equipment), inside utility facilities and in the public spaces of smart cities. MITM hackers can leverage this processing power to wreak havoc in various ways.

Another possible avenue for MITM attacks lies in the growing popularity of the “do-it-yourself maker” movement and the use of easy-to-use platforms such as Raspberry Pi and Arduino. Please note – we are not impugning Raspberry Pi or Arduino in any way here, on the contrary, SAM loves these platforms J, we merely wish to highlight possible security implications of using what are rather powerful tools that are making electronics more accessible and resulting in quite a number of “cool” applications.

Potential Inadvertent Risks Posed by Open Community Hobbyists

For the hobbyists using these platforms and connecting their devices into their home networks, the peril lies in the open community nature of them. Open and community-based hardware is sold for a one-time cost, which covers the R&D, manufacturing, overheads and profit for these devices. However, the price cannot pay for security, which is an on-going item. To be clear, the issue is not the open source (open source is a good thing). The issue is that anyone can build (code and develop) a “project” for a platform like Raspberry Pi and then that person, and others, can use this project, for example, to create a “home ad block.” But while this project accomplishes its goals (e.g., to block ads on the entire home network) in many cases it does not take care of security and will leave a backdoor wide open.

Every system has vulnerabilities, and this includes IoT devices which usually have minimal or no security measures after they become active on an office or home network. This exposes users to many types of attacks. In addition, shortening hardware products development cycles means that less mature products, in terms of firmware, are released to the market. As noted above in discussing devices with increased embedded processing power, this becomes even more of a potential problem in the age of raspberry-pi and Arduino-based prototyping, which incorporates fairly powerful hardware on the one hand, but has low security measures on the other. Therefore, these hobbyists could be enhancing existing devices or creating new ones, but inadvertently creating security gaps as well.

Therefore, what should one do to detect and prevent MITM attacks? Most importantly, a user should always make sure that the OS of the devices in a network (mainly PCs and smartphones) is updated and that all web browsers are kept up to date. When browsing a website, check that it’s a secure “HTTPS” URL and that a “lock” symbol is present whenever sensitive information could be transmitted, e.g., a bank website or email portal. Lastly, make sure your network devices, especially routers, don’t use default or weak credentials such as admin, admin123 etc. A compromised device has the potential to become a MITM actor.

And as for the ISP network that connects the user to the Internet and more, the ISP should have network security measures in place, such as deep network visibility to accurately identify all IoT and other devices connected to it, to prevent the exploitation of vulnerabilities caused by non-existent built-in security. In that vein, network service providers should actively and continuously update their network security policies using such solutions, as thousands of new IoT devices are being added to networks each day.